In a casual game of craps, there are usually two bets: win or lose. Payout on either is 2:1. Betting takes place before the first roll, at which time the player holding the dice has a consistent, slight disadvantage versus the players betting against him. In a casino, there are many possible bets on a craps table. Payouts vary from 2:1 to 19:2, and house advantage varies from “sucker bet” to “keep ’em there long enough to buy dinner.”

But every bet, even the sucker bets, has an identical, simple design: the minimum house advantage payable in whole chips. Variation in odds is not due to some elaborate strategy on the part of the casino, but to the limited number of chip denominations and characteristics of the infinite-but-partitionable potential sequences of die rolls.

Why the minimum house advantage? That’s a part of the other game the casino is playing: don’t just make the player lose, keep the player losing.

Everything on the table is controlled by just two dice. To win the second game, the casino has to manage light, temperature, sound, color, the portion size of complimentary drinks and 100 more.

The game on the table hasn’t changed with the digital age. The game in the casino has, but the critical difference isn’t the number of factors, or even the complexity.

I’ll come back to that critical difference. But first … we’ll have to loosly define a few math terms.

Continuous vs. Discrete

Continuous

: comprised of uncountable parts, infinitely divisible.

If I pour water into a glass, the volume is continuous. In other words, there are infinite[1] possible volumes between 0 and full:

- 1/3 of a cup

- 1/3 of 1/3 of 1/3 of 1/3 of a cup

- 99.9999999% of a cup

- and so on ……………………… forever.

Discrete

: comprised of countable parts.

If I put marbles into a glass, the volume is discrete. In other words, there are finite possible volumes between 0 and full:

- 0 marbles

- 1 marble

- 2 marbles

- up to maybe 30 marbles depending on the size of my glass.

[1] Volume of water isn’t strictly continuous (it’s made of countable molecules). Only things like acceleration, bias, and risk are strictly continuous. But water of sufficient volume is effectively continuous, so we treat it that way—even in equations.

And that’s the way I’m using continuous and discrete here: effectively continuous and effectively discrete. On the King Ranch (world’s largest ranch), cattle population is effectively continuous. In my back yard, cattle population is discrete.

I’ve paused to highlight the “effective” distinction because I’ll be using the particularly non-mathematical term “very discrete.” The “more discrete” a quantity is, the less effectively it can approximate a continuous value. For instance, you can stand on a stack of books to change any lightbulb, but you can’t reach most lightbulbs from a stack of libraries.

Continuous and discrete measurements can “predict” each other

Given the volume of barking in my driveway (continuous), we could estimate the number of dogs (discrete) living in my neighborhood.

Given the number of barks heard in 24 hours (discrete), we could estimate the amount of time (continuous) those dogs spend outdoors.

The continuous adapts well to the discrete

A catering service can estimate how much food (continuous) to cook for 5 people (discrete).

But the very discrete does not adapt well to the continuous

How many cows are needed to yield at least 1 lb of meat?

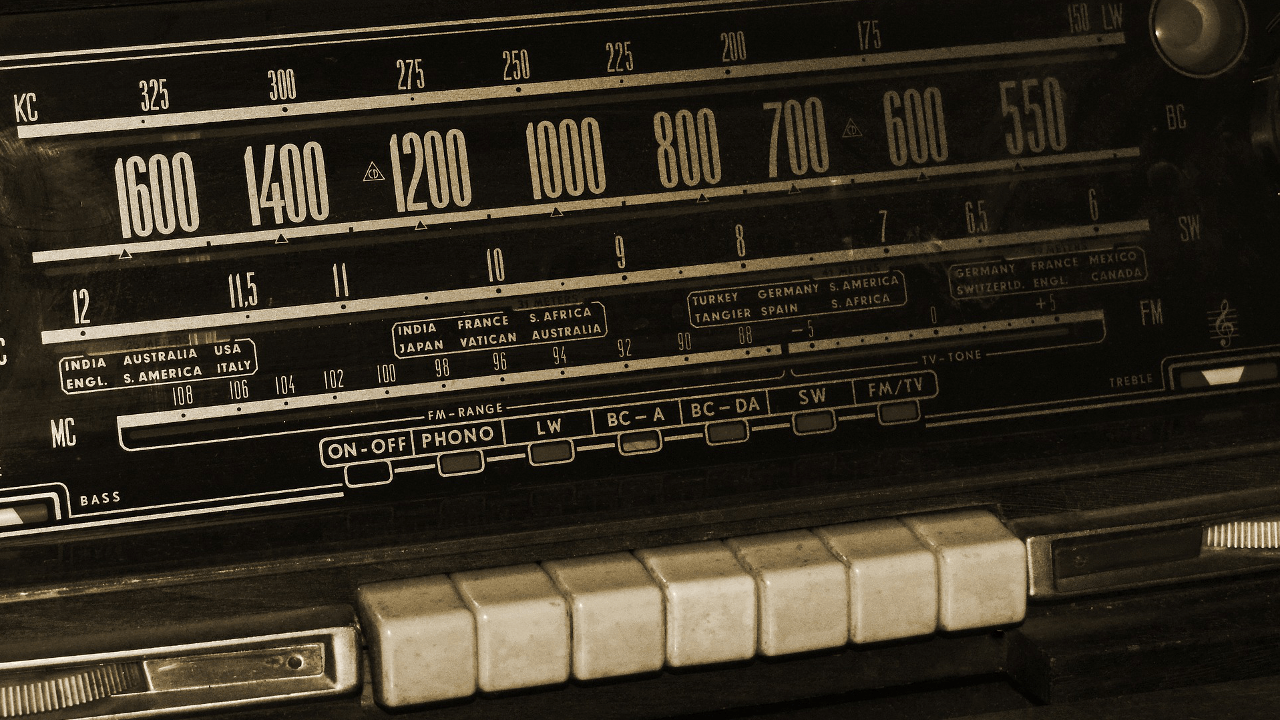

In short, we can tune to a station a whole lot better than we can station to a tuning

And that’s where we get in trouble. Another example:

You make a plan to drive 100 miles to a friend’s wedding. You check the price of gasoline and budget $4 per gallon. As the wedding approaches, the price of gasoline rises 10%.

If the trip were continuous, you’d simply take less trip. You would drive only 91 miles and still make your budget. You’d miss the wedding anyway, but you’d be comforted by the fact that you’d made a data-driven decision.

Your real choices are discrete:

- stay home

- increase your budget

“Increase your budget” is a tempting solution, because you’ve found a continuous piece to this puzzle. You could take just the right amount of continuous (and fungible!) money from somewhere else (or a dozen somewheres else) and leave the minimum possible continuous hole(s).

But what if money were discrete? What if you were paying in gold bricks? What if a 10% increase in gasoline weren’t a few more dollars, but another gold brick?

That’s the situation we often face when trying to alter operations and move personnel (a discrete resource) in response to single-digit analytical revelations.

Back to the craps table

“Single-digit analytical revelations” are what machine learning provides. Some combination of some things correlates with a small effect somewhere. Once we filter out the “some things” outside our control, the effect is even smaller. (Where these effects are on a boundary, e.g., “has cancer?”, the significance in tremendous).

The casino is definitely in control of the environment inside the casino. They can turn continuous knobs, tweak continuous jiggers, and continuously shift things around to maximize even a small effect.

The casino is also in control of the game (craps), but the game doesn’t have any continuous knobs. Machine learning might reveal (might have already revealed) that players are more likely to leave and never return after three losses in two hours on “hard 8.” But what can the casino do with that information?

They can’t provide less loss. They can’t shift the odds toward the player’s favor without shifting the odds to the player’s favor. The casino has to pay the player in (discrete) chips. To return to a previous metaphor, they’re either too high or too low to reach the lightbulb.

The takeaway?

Machine learning and advanced probabilistic models require a lot of data. Applying ML requires a lot of (granular) control. The second is not a problem for investment markets for reasons that should be obvious by now, but it can definitely be a problem for those of us who more often have to decide “how many?” than “how much?”

For the discrete choices we face, there will never be an “aim small.” Small revelations should not compel us to swift action. In these domains, what we already know may be more important than what we will ever learn.

If you enjoy topics like this, please subscribe. And check out

- Matti Heino‘s articles on probability, complexity, social science methodology, and research transparency.

- Aerin Kim‘s somewhat-lower-level “notepad for Applied Math / CS / Deep Learning topics.”

- Nancy Pi‘s even-lower-level whiteboard talks on all the Calculus you might have slept (or cried) through in school.