I have two coins. One coin is a normal, fair coin, with heads on one side, tails on the other, and 50% chance to land on either side when tossed. The other coin is special. The special coin has a head on both sides. No matter how many times you toss the special coin, you will always see heads.

I give you one of the coins and allow you to toss it one time. It lands on heads. Which coin did you get?

The slightly clever answer is that I probably gave you the two-headed coin. If you have a little math, you might explain it this way:

There are \(3\) ways to get heads: \(2\) ways on the two-headed coin, and \(1\) way on the normal coin.

\[\frac{2\ heads}{3\ heads}\]That’s a \(2/3\) chance I gave you the special coin.

If that were right, I’d end this article here. To be fair, it isn’t entirely wrong. Thomas Bayes published something similar 250 years ago, and he’s still famous for it today.

But there’s a big hole in our logic. If you haven’t spotted it yet, read back through and see if you can find where we went wrong.

Did you see it? What did we miss? Let’s take a literal look at our thinking.

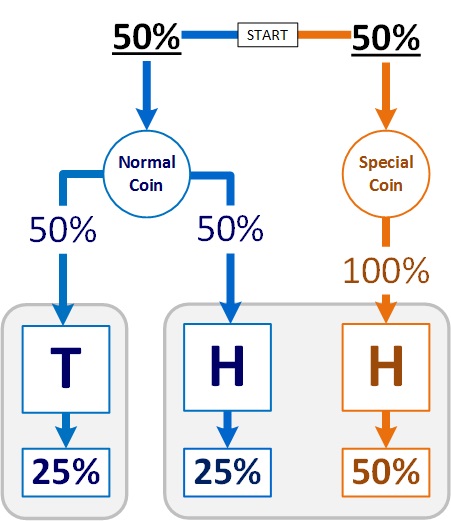

This image is a model of our coin game.

Two Coins

- a normal coin with 50% chance to land on either heads or tails.

- a special coin with 100% chance to land on heads.

Two Possible Results

- tails – 1/1 chance you got the normal coin.

- heads – 2/3 (50% / 75%) chance you got the special coin.

I’m sure you’ve seen the error by now: much of this assumes a 50% chance (underlined in the picture) that I’d give you either coin.

The game did not begin with “You receive a coin at random” or even “You pick a coin.” No, I picked the coin, and you don’t know me well enough to know how often I’d just give away my special coin.

because in real life, the question is rarely “What did I get?”, rather “How do I [not] get it again?”

Back to that underlined 50%. In probability terms, we assumed a prior of 50%. We didn’t have any reason to (actually, we did; keep reading), but we had to choose something.

The word “assume” has an ugly connotation. Instead of “assumed”, let’s use “estimated”. We’ll say that we estimated a prior of 50%. As estimates go, 50% isn’t bad. By picking the exact middle, we will at most be “half wrong”. Right?

So, given 50% as a starting point, where can we go?

Here’s where it hurts. You’ll need over 1000 turns to approach a prior with any useful measure of confidence.

Here’s that sentence again.

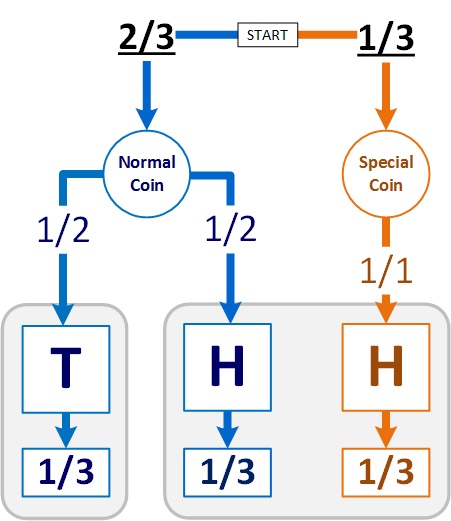

Let’s look at a specific example. I will give you the special coin 1/3 of the time. So, p is 1/3, but you won’t know that. You have to play the game to estimate how often I give you the special coin.

Your strategy, as above:

- Tails means you definitely got the normal coin.

- Heads means a

p%chance that you got the special coin.

Starting with no information (prior = 50%), 1000 turns would give you a 69% chance of estimating within 3%.

That is, you’d have a reasonable chance at a decent guess—after 1000 turns. And you’d better have one Hell of a margin to come out ahead on a guess like that—after 1000 turns.

If I were stingier with my special coin, your odds would be even worse.

The point is clear: even this simple game of inference requires a LOT of data. There’s a very good reason we’ve had Bayes’ Theorem for 250 years, but we’ve only had analysts (or teams of analysts) at every corner store and laundromat for maybe 10.

Computers, of course, but even the best computers need something to count (and the best analysts something to chart)—we need lots and lots of turns at the game. To this end, we “borrow” turns from similar games: previous elections, industry-wide data, experiments on mice, etc.

There are two problems with that. The first is obvious and mitigable, and you’ve already thought if it: things will have changed.

The second is less obvious, but often more important: the things that haven’t changed most likely can’t change. This is fine (great, actually) if you’re trying to predict the future, but terrible if you’re trying to change the future.

The biggest surprise of all may be that—in a few domains—any of this actually works.

If you’re Google, Amazon, or Walmart, this need for data won’t be a problem. If you’ve lost eight fingers and you’re trying to save the other two, data science may not have any answers for you.

If you enjoy topics like this, please subscribe. And check out

- Matti Heino‘s articles on probability, complexity, social science methodology, and research transparency.

- Nancy Pi‘s even-lower-level whiteboard talks on all the Calculus you might have slept (or cried) through in school.