Sir Tony Hoare invented quicksort to alphabetize lists of Russian words.

When most of us sit down to alphabetize a list we

- pick one item;

- decide if the next goes before or after;

- decide if the next goes before, after, or in between;

- …

That’s called “insertion sort”, and it does get the job done, but Sir Tony needed a faster way.

Quicksort

Here I’ll use English letters for Russian words.

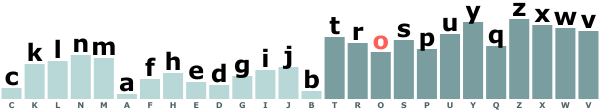

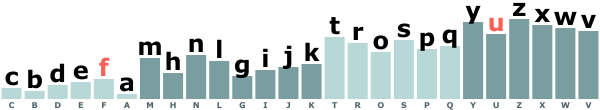

The first thing Sir Tony did was pick a word (the pivot) from his list. He then separated the remaining words into two groups: words that come before the pivot, and words that come after. The pivot could fall into either group.

That left a low group and a high group, but the groups themselves were still not sorted. So Sir Tony split each of the new groups as he had the full list: by selecting a pivot, then dividing into before and after.

And again and again and again. We can already see the sort happening; our list will be sorted in a few more splits. And what we’ve just watched is essentially the fastest known way to sort a list of Russian words (or anything else).

Simple, right? That’s the curious thing, and I’ll get back to it soon, but first…

What a Rat Knows

When my son, Oliver, was around 1-year old, I listened to a course, “Scientific Secrets for Raising Kids Who Thrive” (Peter M. Vishton). In the course, Dr. Vishton described how rats can and cannot navigate.

Rats were conditioned to search for food in one corner of a rectangular box. Afterward, each rat was tested by

- removing the rat;

- spinning the box around; then

- placing the rat back in the box.

Each rat immediately ran to the corners, looking for food. The test was which corner the rat searched first.

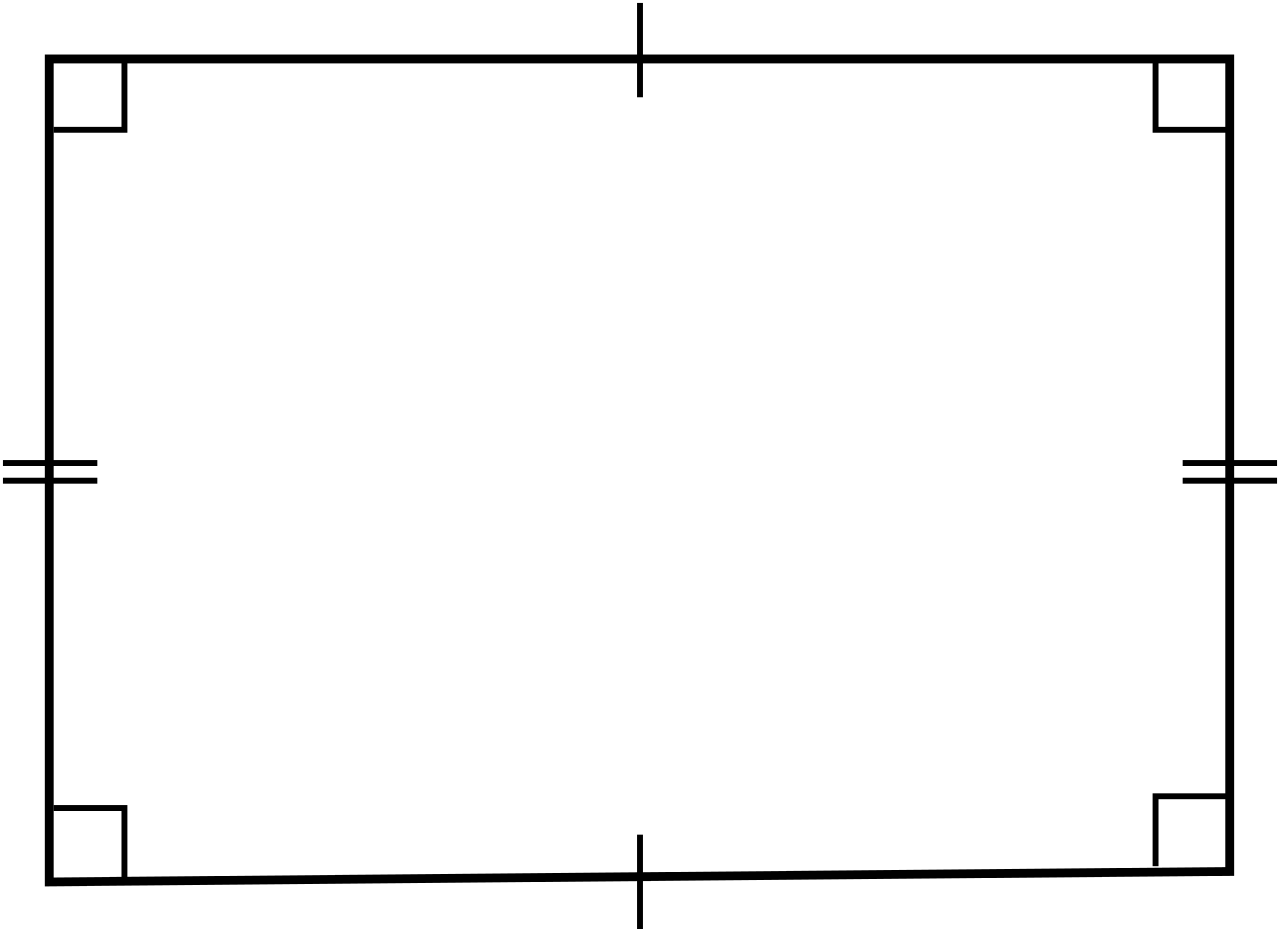

Of course, any given corner in a rectangular box will have

- a short side on the left and a long side on the right; or

- a long side on the left and a short side on the right.

But this didn’t help the rats. On average, the rats guessed correctly only 1 out of 4 tries—no better than random luck.

Splash on a Little Paint

In a similar trial, rats were again conditioned to search for food in one corner of a box, again removed, again disoriented, and again placed back in the box.

This time, the short sides of the box were painted blue and the long sides red. This did help the rats. A rat knows the difference between

- blue on the left, red on the right; and

- red on the left, blue on the right.

Painting the sides of the box increased the rats’ chances to nearly 1 in 2.

So, a rat has some rudimentary (at least) concept of left and right. And a rat can see depth as well as color. And a rat has intelligence. And a rat can put these together in certain ways. But a rat can only put these together in certain ways. Something is missing.

What does this have to do with raising kids who thrive?

A human child under 18-months old has the same problem as the rat. That is, the child can navigate by color, but not by depth.

Unless…

… the child has learned the words “left” and “right”. According to the course, just naming these concepts unlocks a child’s ability to navigate by depth!

How Cool is That?!

This was before the replication crisis, but I believed it then and it still “rings true” today. Whether the rat study was actual evidence or just the exact metaphor I needed, hearing about it was revelatory.

I’d already been working with Oliver on left and right, but another “missing piece” came immediately to mind … zero. We’d never have gotten past the abacus without zero, and it seems like the most obvious possible concept, but some otherwise brilliant westerners missed or dismissed zero for over a thousand years.

From the moment I recognized zero as a very-non-obvious concept, the terms “none” and “not any” were verboten in our home. The “not any” answer to “how much” or “how many” was always “zero”. An empty plate had zero bites, and an empty bottle had zero sips.

Maybe this bit of pedantry helped, and maybe it didn’t. But I did what I thought was best.

Between Then and Now

I have been looking for such missing pieces ever since, and the probability and writing sections of this site are a partial catalog of what I’ve found: concepts that seem obvious after they’ve been revealed, but somehow eluded humanity for millennia or elude most of us today.

The Curious Thing About Quicksort?

Quicksort is one such missing piece. It’s dead simple, I understood it instantly and completely after seeing it for the first time … and yet, it never occurred to me. I had to be told. And even now that I have been told, it doesn’t occur to me to use quicksort outside of programming.

And I’m not the only one who had to be told. Quicksort wasn’t documented till 1961.

I’ve selected the word “documented” carefully, because it’s tempting to quibble, to say, “Just because no one wrote it down doesn’t mean no one ever thought of it.” So, let’s make a fair comparison:

- quadratic equations were documented in 8th century BC

- pi was documented in 6th century BC

- trigonometry was documented in 2nd century BC

- differential calculus was documented in 12th century AD

- general relativity was documented in 1916

- we **still had to wait another 45 years for quicksort**

And we weren’t waiting for computers to need quicksort. The goal of any computer sorting algorithm is to minimize binary (a vs. b) comparisons, and this might have been even more important when the world was measured on binary scales.

Despite a strong intuition to the contrary, quicksort is obviously less intuitive than it seems. This suggests it may be a missing piece of a much less obvious (for now) revelation. Go quicksort your books, music, or spice rack immediately; you might be more human and less rat afterward.

I’m Still Searching

If you know of other such missing pieces—algorithms or relationships anyone can understand, but few people do (or historically few people have)—please let me know. I’m easy to reach.