Count Like a Player

This started off as a brief explanation in another letter (There is No Objective Reason to Avoid the Lottery). By the time I was done, the non-objective portion was overwhelmed. Here it is on its own. For a brief explanation, it’s a complete failure, but these 1500 words will take you all the way from fourth grade (+ – * /) to easily talking yourself out of the lottery. (First make sure you want to!) Keep this handy, and you’ll be able to answer most “What are the chances” or “If you pull 5 whatever out of a bag” questions you may come across.

Let’s first look at a few ways of counting groups.

Counting 1 – count like books

How many ways can you line up three books on a shelf?

- Order matters.

- Every book is unique.

We count these with factorial, written \(N!\) where \(N\) is the number of books.

\(N!\) is the same as \(1 * 2 * 3 ... *\ N\)

Let’s test it. How many ways can you line up 3 books?

That works! Here are the 6 ways to line up your 3 books.

|

|

|

|

|

|

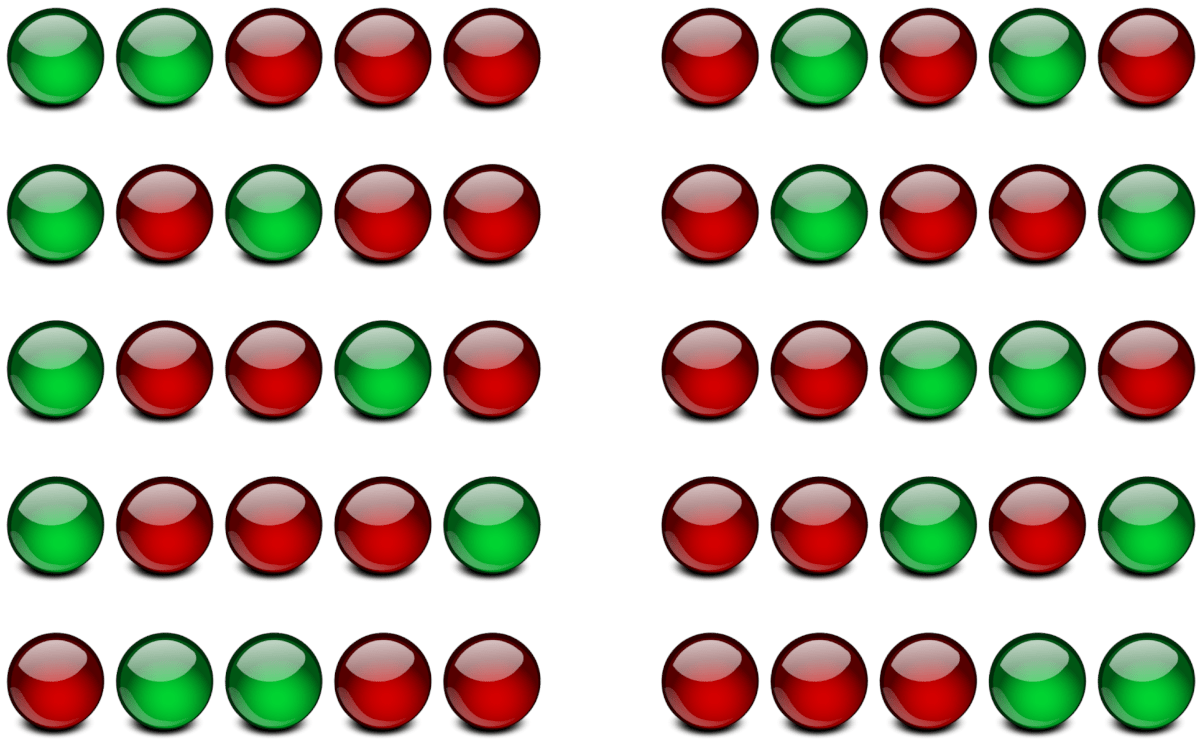

Counting 2 – count like marbles

How many ways can you line up 2 green marbles and 3 red marbles?

- Order matters.

- All marbles of the same color are equivalent.

5 marbles total. If every marble were unique, we’d be able to line them up \(5! = 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 * 5 = 120\) different ways. We’ll start there.

That’s obviously too high. It looks like we’re counting each arrangement 12 times. Let’s take a closer look at that first column, but this time we’ll name our marbles so we can see what’s going on.

Our two green marbles will be A and B and our three red marbles C, D, and E. Here’s the first column again.

A B C D E

A B C E D

A B D C E

A B D E C

A B E C D

A B E D C

B A C D E

B A C E D

B A D C E

B A D E C

B A E C D

B A E D C

As you can see, there are 2 (\(2!\)) ways to line up “green green” and 6 (\(3!\)) ways to line up “red red red”.

The order of identically colored marbles doesn’t matter. So, divide 120 by \(2!\) for the green marble orders then divide again by \(3!\) for the red marble orders.

In general, for every color of marble, divide by \(M_n!\) where \(M_n\) is the number of marbles of that color.

Let’s test it. How many ways can you arrange 2 green marbles and 3 red marbles? \(n\) is the total number of marbles. \(M_1, M_2, M_3 \dots\) are the number of identical marbles for each color.

That works! The 10 possible arrangements are

\(\frac{n!}{n_1! \quad * \quad n_2! \quad * \quad n_3! \quad \dots}\) will work with any number of colors. Exactly 2 colors is a special case \(\frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\) where \(k\) is the number of red or green marbles (the equation works either way). This is known as “\(n\) choose \(k\)” and written \(n \choose k\).

Let’s test it. How many ways can you line up 2 green marbles and 3 red marbles?

That works!

Counting 3 – count like cards

How many 2-card hands can you draw from a 5-card deck?

- Each card is unique.

- Order doesn’t matter.

Start with all possible ways to line up our full deck of 5 cards. That’s \(5! = n! = 1 * 2 * 3 * 4 * 5 = 120\) possible arrangements. Take the first two cards of each arrangement for your hand. Blue numbers are the cards in your hand. Red numbers are the cards remaining in the deck.

1 2 | 3 4 5

1 2 | 3 5 4

1 2 | 4 3 5

1 2 | 4 5 3

1 2 | 5 3 4

1 2 | 5 4 3

1 3 | 2 4 5

1 3 | 2 5 4

1 3 | 4 2 5

…

111 more arrangements to go, but we can already see a pattern. The first six arrangements leave the same two cards in your hand. That’s because the order of the cards left in the deck doesn’t matter. So, we can divide our 120 possible arrangements by \(3! = 6\) ways we could arrange the cards left in the deck. This brings us down to \(5! / 3! = 20\) arrangements.

| 1 2|* * * | 2 1|* * * | 3 1|* * * | 4 1|* * * | 5 1|* * * |

| 1 3|* * * | 2 3|* * * | 3 2|* * * | 4 2|* * * | 5 2|* * * |

| 1 4|* * * | 2 4|* * * | 3 4|* * * | 4 3|* * * | 5 3|* * * |

| 1 5|* * * | 2 5|* * * | 3 5|* * * | 4 5|* * * | 5 4|* * * |

We have accounted for the fact that the order of the cards left in the deck doesn’t matter. Now … the order of the cards in your hand doesn’t matter either. 12 is the same hand as 21. To account for this, we’ll divide our 20 by \(2!\). That brings us to \(20 / 2! = 10\) hands.

This is marble counting where the total number of marbes will be the number of cards in the deck, and you will always have 2 “colors” of “marbles”: the “marbles” in your hand and the “marbles” left in the deck.

The answer to “how many groups of \(k\) can I select from a group of \(n\) unique items” will always be \(n \choose k\).

Let’s test it. How many 2-card hands can you draw from a deck of five cards?

That works! Our 10 possible hands are 12, 13, 14, 15, 23, 24, 25, 34, 35, 45.

Here’s a real-world example: how many possible 5-card hands might be drawn from a 52-card deck?

Now that we know how to count

Now that we know how to count, we just have to choose we want to count. This kind of probability is simple:

\(\mathbf{\frac {positive}{possible}}\). Count the positive, then count the possible, and you’ll have the odds.

Odds of winning the lottery

- \(1\) positive outcome

- \(n \choose k\) possible outcomes (each ticket is a “hand” of numbers) where \(n\) is the number of lottery balls and \(k\) is the number of balls chosen.

Let’s test it. We’ll set up a tiny lottery. To pick a winner, we draw three numbers from a bowl of four numbers. If those three numbers match the three numbers on your ticket, you win.

That works! Our 4 possible picks are 123, 124, 134, and 234.

Here’s a real-world example: the odds of winning Lotto Texas (pick 6 numbers from 54) are