When you write about math, your friends and family very often want to ask about “The Chances.” The Chances are the dark side of probability. “What are The Chances?” is only a question in the rhetorical sense. “What are The Chances?” is, in fact, an accusation. “What are The Chances?” means “I know someone cheated.”

- What are The Chances the lottery winner would work in the state capitol building?

- What are The Chances my coworker’s house was the only one to burn down … in a flood?

- What are The Chances the neighbor would break his leg in a five-mile-per-hour collision?

- What are The Chances Bridget would win all three games of Bingo last Saturday night?

It’s Christmas, so, in the spirit of charity and good will, let’s take a look at that last one

The pedantic answer is easy. With 100 people playing Bingo,

- 1/100 chance Bridget wins the first game.

- 1/100 chance Bridget wins the second game.

- 1/100 chance Bridget wins the third game.

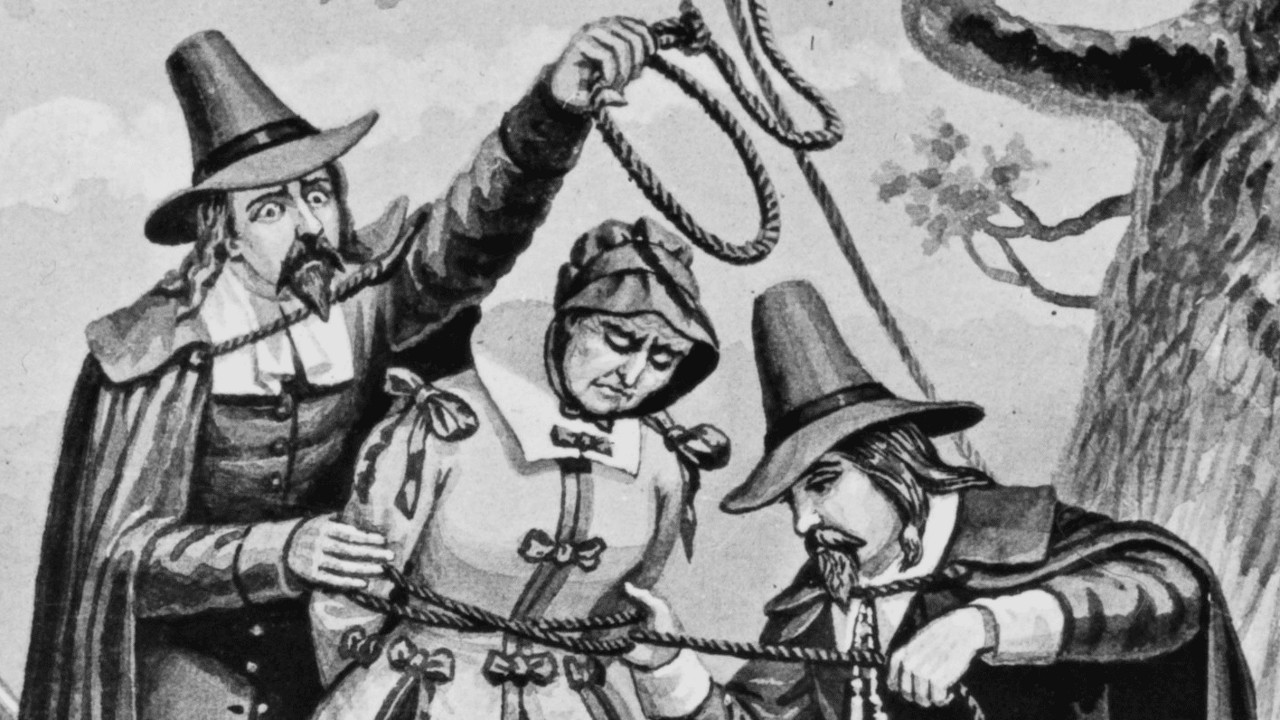

The Chances Bridget won all three games of Bingo last Saturday are one in a million. Bridget is obviously a witch!

Does it have to be Bridget?

One in a million is the answer to the question as asked. But the intended question might be “What are The Chances any one person would win all three games of Bingo last Saturday.” Those odds are much better than one in a million.

- 100% chance someone wins the first game.

- 1/100 chance the same someone wins the second game.

- 1/100 chance the same someone wins the third game.

Things are already looking a little less nefarious. But 1:10,000 is still a pretty small chance. You’ll probably be talking about this for years, which invites the question …

Does it have to be last Saturday?

Will we still be talking about Bridget’s “impossible” streak in 100 Saturdays? If so, then which of the 100 Saturdays isn’t important.

The math for this one is a bit trickier.

Where:

- \(p\) is the chance of success per trial

- \(n\) is the number of tries

- \(k\) is the number of successes

That is the probability mass function of a binomial distribution. I’m only writing that out so you can find it later on Wikipedia. A more appropriate description is “What are The Chances of winning \(k\) times in \(n\) tries?”

It’s actually a little more formula than we need here, but keep it handy and you’ll usually be able to figure out The Chances even when there are no math bloggers around.

Let’s set our variables.

- \(p = \frac{1}{10,000}\) is the chance of any one person’s winning all three games on a particular Saturday.

- \(n = 100\) is the number of Saturdays.

- \(k = 0\) is the number of successes. Why \(0\)? That leads into the ungainly, but pretty much necessary explanation found in every probability article.

We’re not talking about it, but there is a small chance we could have more than one “impossible” Saturday. In that case, we’d have to figure out The Chances for exactly 1 impossible Saturday + The Chances for exactly 2 impossible Saturdays + … all the way up to 100. Instead, we’ll start with a 100% chance and subtract the chance of 0 “impossible” Saturdays.

We’re all the way down to a reasonable (1%) chance Bridget’s “impossible” Saturday happened without forged cards, slight of hand, bribing the Bingo caller, or other such witchcraft. Were we a little quick to judge Bridget?

Before you answer …

We’ve already decided that it didn’t have to be Bridget and it didn’t have to be last Saturday. Did it have to be Bingo?

Every time we roll dice, flip coins, deal cards, buy stocks, draw Scrabble letters, kick a ball, name a pet, skip a rock, change the channel, open the curtains, answer an anonymous phone call, guess a number, hold a raffle, drop a glass bottle, throw trash into a far-away basket, or close our eyes and spin around, there is a small-but-probably-larger-than-we-suspect chance to see something “impossible.”

Here’s one more time through our formula

- \(p = \frac{1}{100}\) chance of “impossible” event per game (a game’s being any witnessed event)

- \(n = 100\) games witnessed 100 times each

- \(k = 0\) “impossible” results

That’s a 63% chance of seeing something “impossible” if you watch 100 games 100 times.

Go apologize to Bridget.